IMAGE SOURCE,NOH JUHAN | NETFLIX

IMAGE SOURCE,NOH JUHAN | NETFLIXTrying to watch some of Netflix’s more recent series all the way through, says Paul Weiner, feels a bit like cramming frankfurters down your throat in a hotdog eating contest.

Readers outside the US may not share the American enthusiasm for competitive hotdog swallowing. But maybe they can relate to the feeling.

We’ve all spent the last few years, the last two especially, binge-watching, indiscriminately, too mesmerised to click the off-button.

Are we maybe just a little bit sick of it?

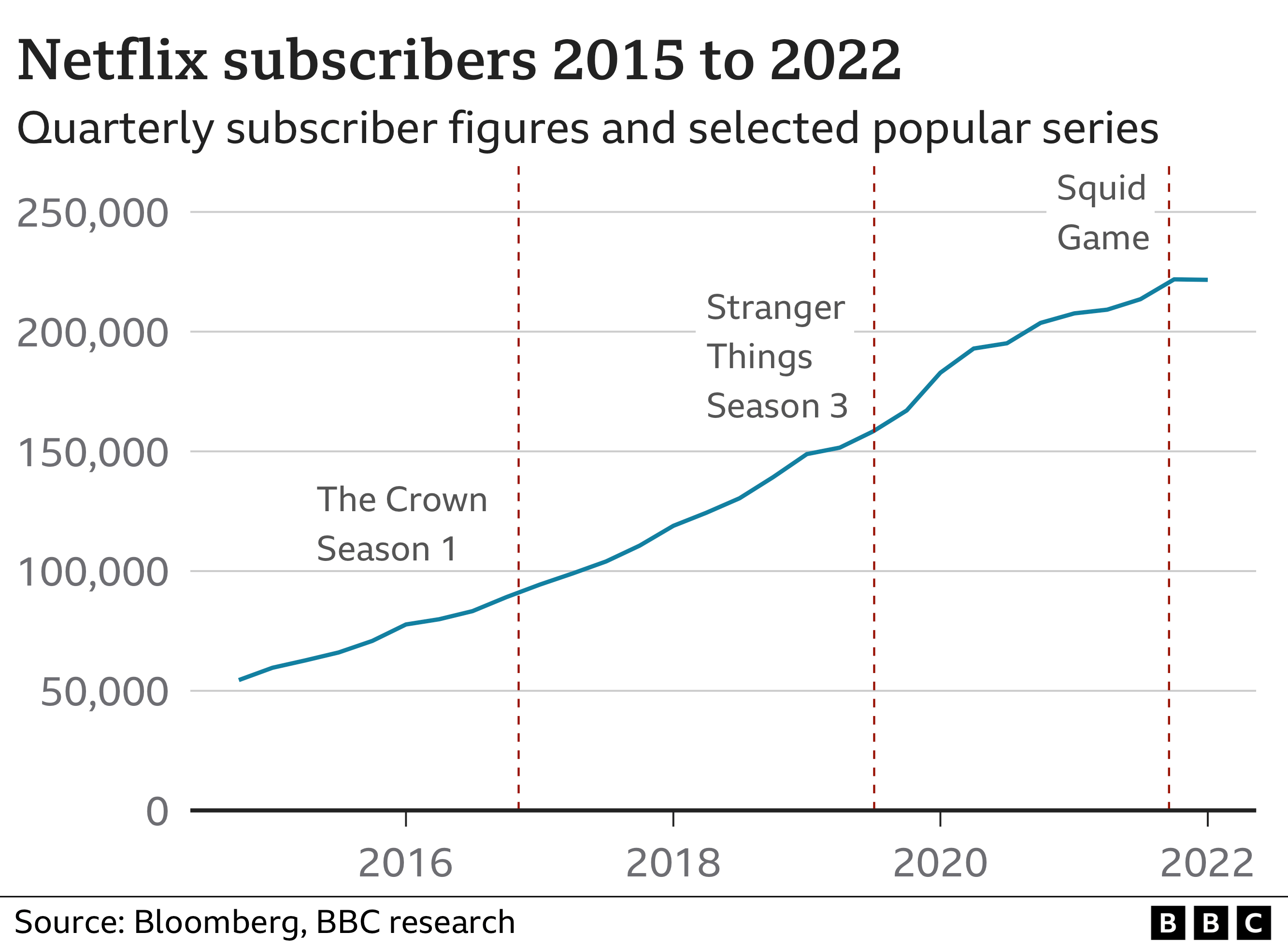

That’s the fear seizing executives in Netflix’s boardroom right now. That Mr Weiner, a 28-year-old artist from Denver, Colorado, who loved the streaming service at first, especially for watching old favourites like Star Trek and The Office, typifies a new mood. That after years of skyrocketing subscriber growth, people will switch off, not just their television sets, but their direct debits too.

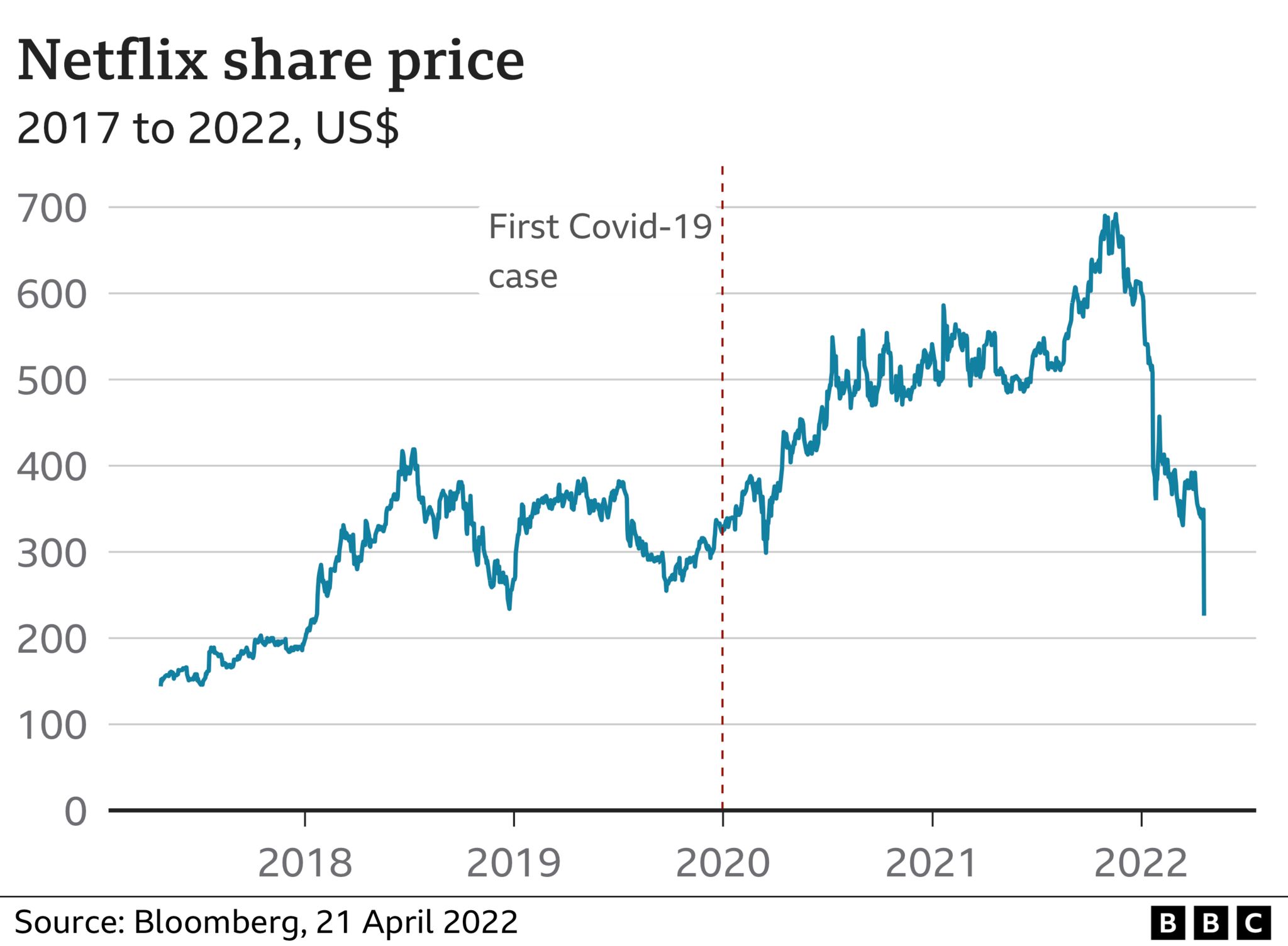

Mr Weiner is one of the hundreds of thousands who have already cancelled, prompting a moment of high drama for the company this week as its share price plummeted and confidence in its future wobbled.

People have begun to ask whether Netflix’s star, as the world’s largest streaming service, is beginning to fade.

IMAGE SOURCE,PAUL WEINER

IMAGE SOURCE,PAUL WEINER“Netflix lost some of my favourite shows,” says Mr Weiner. “And I never know which show will disappear next.”

He thinks there’s more clickbait than there was – enticing teaser clips that don’t live up to expectations – and some poor writing.

“There are better streaming deals than Netflix right now,” he says.

Netflix was the first to introduce households to TV-on-tap in 2007, entering popular culture with its avalanche of output, and even spawning the phrase “Netflix and chill” as a euphemism for staying in to have sex. But since then many other streaming services have followed Netflix’s lead, including HBO, Disney, Apple and Amazon, making it an increasingly crowded market.

“What made Netflix so popular initially was not necessarily its original programming, but the shows it licensed from other production companies, like Friends, giving viewers one convenient place to watch everything they love,” says entertainment journalist Tufayel Ahmed.

“With companies now taking their shows off the service and putting them on their own streaming platforms, Netflix faces the problem of having to fill the gap.”

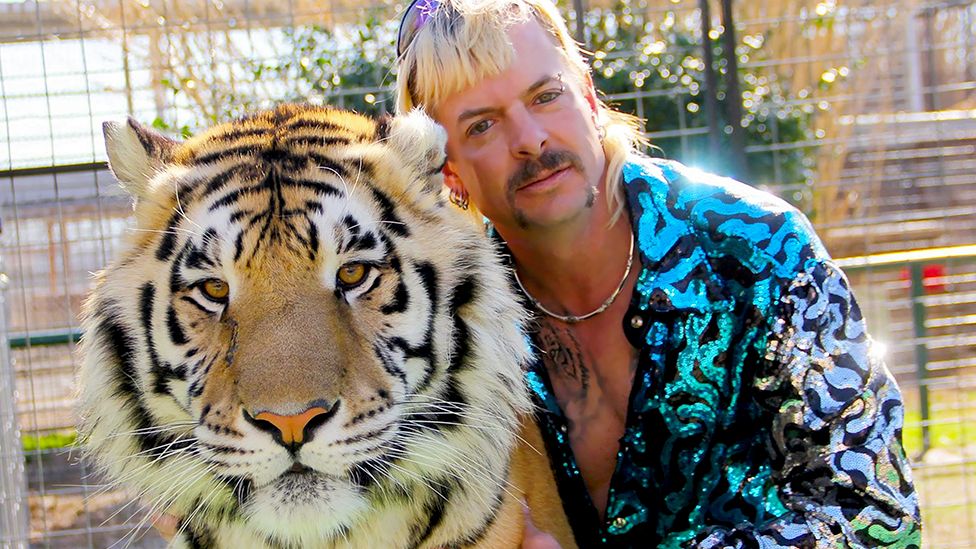

They’ve done that, launching some hugely successful original output, from the lurid regency romp Bridgerton to the brutal Squid Game, high school comedy Sex Education to the touching drama Afterlife. Sixteen million people signed up in three months at the start of 2020 as coronavirus spread the world and discussing the dubious morality of Tiger King or the historical accuracy of The Crown was a way to switch off from the horror show of the news.

But with so many rivals, “all of which are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into competing with Netflix”, says Mr Ahmed, it was almost inevitable the company would eventually lose some ground.

Mark Mulligan, media analyst at MIDiA Research agrees, pointing to a trend for “savvy switchers” to skip between services.

“Everyone had more time and cash during the pandemic which meant the market was artificially buoyant,” he says.

But now he thinks: “The economy for people’s attention has peaked and the amount of spare time people have has run out”.

IMAGE SOURCE,NETFLIX

IMAGE SOURCE,NETFLIXThere is also a cost of living crisis to contend with, right around the world. And Netflix, rather than lowering prices has raised them, a move that should help shore up the balance sheet, but has proved unpopular with subscribers, who are themselves feeling the pinch, like 38-year-old Natalie Walters from Catford in South-East London.

She hasn’t cancelled, but she’s switched from the premium service, which in the UK costs £15.99 a month, to the standard version at £10.99.

“It becomes about choosing what you keep and what you have to cut down or get rid of altogether,” she says.

IMAGE SOURCE,NATALIE WALTERS

IMAGE SOURCE,NATALIE WALTERSAnd 55-year-old Peter Biggins, a coordinator from Norwich has done the same.

“I’ve been with them from the beginning. They have some good shows, but they’re not the only player in the market now,” he says.

And he’s not a fan of the other plan Netflix is reported to be contemplating: cracking down on customers who share passwords with other households.

“If Netflix is going to go after people who have a subscription, they’re going to annoy them,” Mr Biggins predicts. And it may not have the outcome they’re hoping for.

Aram Asai Munoz, a law student in Santiago, Chile, has shared a Netflix account with his parents and sister, who live in separate households, for several years.

Since he first signed up – eager to tune in to crime drama Better Call Saul – the monthly cost of the service has roughly doubled, he says.

Many of his friends have already cancelled over the price hikes and quality of content and he says he might well do the same if the firm does clamp down on password sharing – after all Netflix is a “frivolity” compared to the other bills that need paying, he says.

“Netflix somehow expects that by forbidding password sharing people will become direct new customers, but economic reality dictates the opposite: they will simply walk away from the service,” he says.

While unpopular with customers, the new strategy of raising prices and clamping down on password sharing could give the company some headroom, says Julian Aquilina, senior TV analyst at the media research firm Enders Analysis, alongside a plan to offer a cheaper service supported by advertising.

But the impact will be limited. A survey of US Netflix users found only 11% used a shared log in. Some 85% were paid subscribers and the rest were on free trials, Kagan Consumer Insights found.

That doesn’t mean Netflix is about to lose too much ground, though, Mr Aquilina says.

“It is not like it is going to fade away anytime soon. It is a great product, people like using it,” he says.

“The question is, how many more people it will reach in the future. Maybe it won’t be as much as people expected – it seems those expectations are being reset.”